The European Solidarity Corps organised a solidarity meetup from June 9-13 in Helsinki, bringing together sixty young people aged 18-30 with ongoing and recently completed EU-funded solidarity projects across Europe. Coordinated by the Finnish National Agency for Education (Opetushallitus) alongside its European partners: European Commission’s SALTO network and other national agencies in Europe, the event focused on the themes of solidarity, democracy, active citizenship, social inclusion and the importance of cultural diversity. As one of the members of Opetushallitus observed, ”We wouldn’t be Finland without our multicultural history.”

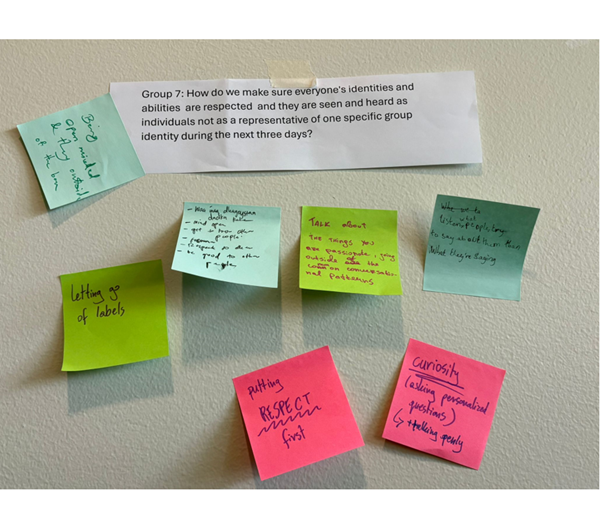

The event successfully engaged young people from across Europe, encouraging them to reflect on their leadership challenges and best practices. In breakout spaces, participants revealed deeply personal motivations behind their social justice work. Many had experienced exclusion from their communities or witnessed similar marginalisation among family and friends, which inspired them to create inclusive spaces. They partnered with NGOs and institutions doing youth work who provided expertise in facilitating brainstorming, grant writing, and project management.

Many participants shared that prior to their experience with the solidarity projects, they did not know much about the concept, nor had they focused on it in as systematic a way as they did after the project. It can be said that young people’s experiences of solidarity emerged from direct experiences of marginalisation as well as from witnessing exclusion among people close to them. Solidarity, therefore, emerged from feelings of empathy and a shared vulnerability. Young people channelled their energy into creating inclusive spaces and building communities where people, especially those who had experienced marginalisation, could come together to express themselves.

Given that many participants were either not aware of or had not seriously considered the concept of solidarity until they began working on their projects, it appears that participating in the solidarity projects provided them with the language to articulate what they might have otherwise intuitively felt or done. However, the process of learning the formally recognised vocabulary accepted by funding agencies also shaped their conceptualisation of specific forms of solidarity that reflected European values of social responsibility, multiculturalism, active citizenship, progressive activism, and participation in a wider political imaginary.

This raises important questions about the dual nature of the institutional vocabulary in solidarity work. While providing young people with recognised terminology enables them to verbalise their thoughts in a language that is valued and understood within European civil society contexts, it also raises concerns about whether such frameworks direct or constrain how solidarity is understood, expressed, and experienced. For example, knowing how to ‘talk the talk’ might privilege certain young people to communicate their work effectively within established systems and successfully acquire funding for their projects, yet it might also potentially influence their understanding of solidarity in terms of institutionally sanctioned forms rather than allowing for more diverse or alternative expressions of collective action and social connection.

Nevertheless, the message delivered by the organisers reflected a genuine commitment to youth empowerment. Through seminars and breakout room activities, participants were encouraged to move beyond their individual selves and think beyond their communities to the wider society and to all of Europe and the world. Young people were encouraged to position themselves as active agents of change, with organisers emphasising ”You are not the future, you are the present and the reality. You are the hope!” This framing positioned European solidarity as achievable through democratic participation – an idea that was further explored in an interesting and informative seminar by Kai Alhanen, director of the Finnish Dialogue Academy. And yet, democratic participation is also an inherently messy and time-consuming process requiring the incorporation of conflicting viewpoints, and decisions might not necessarily be inclusive of all voices.

Discussing the various facilitating and limiting aspects of democracy and solidarity with young people might help prepare them better to face the challenges they are likely to encounter in their work so that they do not become discouraged in the face of setbacks. Perhaps a fundamental question to ask of young people is how it feels to come of age within increasingly complex social contexts – whether they feel that the responsibility of collective action rests on their shoulders. To what extent are their ideas of solidarity a response to the cultural, social, and political worlds they must navigate, and how much represents their active construction of alternative forms of social connection?

By Ayeshah Émon