Virtual art galleries – which had endured a quiet existence before 2020 – became more popular and technologically more sophisticated during and after the global COVID-19 pandemic, when galleries and museums all over the world had to close their doors for several months or even years.

Now galleries and museums have opened their doors once again, but the world has moved into a more digital era even in art deals. According to statistics gathered by Art Basel (https://www.artbasel.com/stories/the-art-basel-and-ubs-global-art-market-report-2025), 22% of art deals were made online in 2024. It does mean that a majority of fine art buyers still want to see the artwork they are buying as a physical object with their own eyes. Still, many dealers have their own websites and online channels.

Hybrid exhibitions with a physical gallery and a virtual gallery side by side make sense for art lovers who want to check works again, or for people who are not able to attend an exhibition. From a gallery owner’s or museum’s point of view, hybrid exhibitions are a sensible choice if the virtual part does not cost them too much extra. Many gallerists, small art dealers and even artists have their own online shops, just as the larger art marketplaces have.

In order to find out in practice how an all-virtual virtual art exhibitions would work – and if it would work at all – the KUVATA project decided to offer professional fine artists and art students in the final years of study a course that included exhibiting one’s works in a virtual gallery. The course ran in autumn 2025, and 15 people originally signed up, with myself acting as the teacher and curator of the works. In addition to this double role, a third one came up as well by the end of the course.

A virtual gallery is not identical to an online digital gallery. A digital gallery resembles an online shop, be it a car dealership, a digital supermarket for retail goods or a clothes shop. The artworks for sale are presented in categories (for instance sculptures, paintings, drawings, by subject etc.) and shown mostly as two-dimensional pictures. Some websites have artificially created room environments where a work of art can be inspected, so that the prospective buyer can get a feeling for its dimensions. After the purchase has been done, the work will be shipped to its buyer. With digital works, the buyer will get an image file to be printed or an NFT to be saved with blockchain technology.

Younger artists and those who also work as illustrators sell their illustrative works as printouts in their own online shops or websites like Artstation, the latter of which also functions as a marketplace, community hub and exhibition space. This kind of artist might also offer services such as painting physical or digital portraits based on customer-sent photographs. However, a better option for a professional fine artist is to get one’s works presented in curated exhibitions, as well as by trustworthy art dealers. Perhaps sadly, selling one’s own works online in one’s own little digital shop is often not seen as the professional thing to do in the world of fine art.

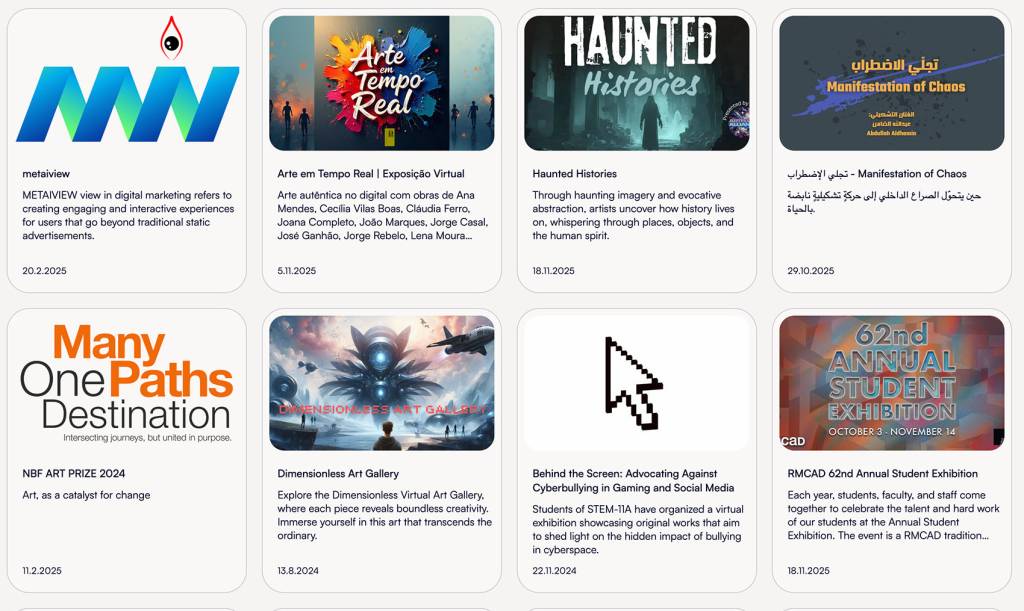

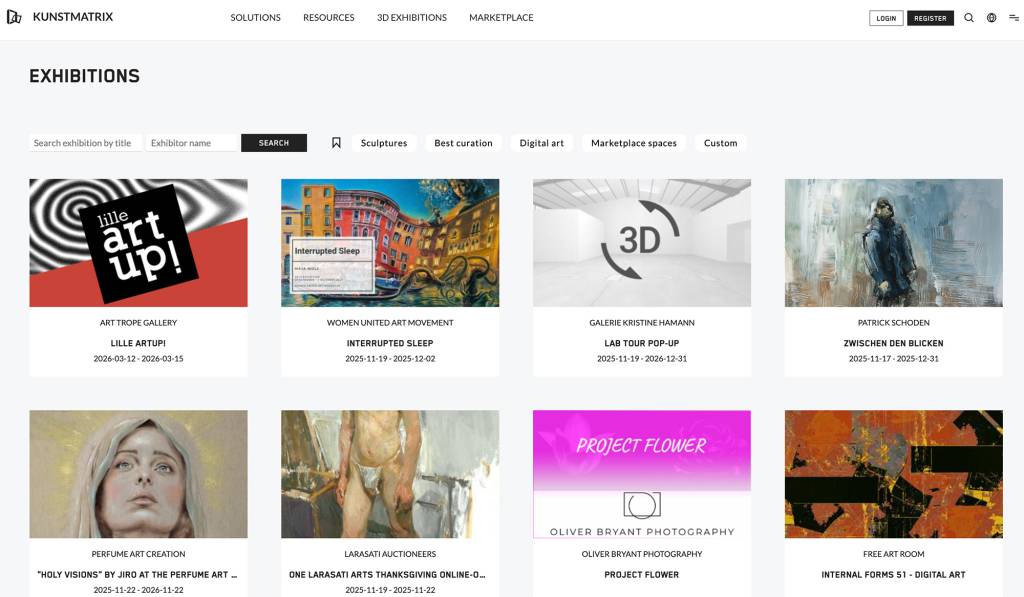

During our KUVATA course, all kinds of digital art dealership were discussed, to understand better where exactly virtual galleries stand in the fine art ecosystem. Do virtual galleries even have a niche that has any meaning? The students chose a few existing virtual galleries and their providers, in order to find out how they worked. We noticed that many virtual art gallery platforms no not have any curation services of their own. Anybody who pays enough can rent a 3D online gallery space. As a result, platforms such as Kunstmatrix (kunstmatrix.com) or Virtualartgallery (https://discover.virtualartgallery.com/) have some exhibitions that do not exhibit actual art. A conference might want to put up their posters and other visual materials in a virtual gallery, for instance.

The students of the course also found out that most virtual exhibitions were designed for a solo visit. Visitors would not be able to see any other people as virtual avatars, nor could they have conversations with anybody. Of course, in physical museums and art galleries visitors are encouraged and directly told to remain mostly silent. This is not the case at large art fairs such as Art Basel, Documenta or the Venice Biennale, or at any exhibition openings, where social mingling and networking are popular and often crucial.

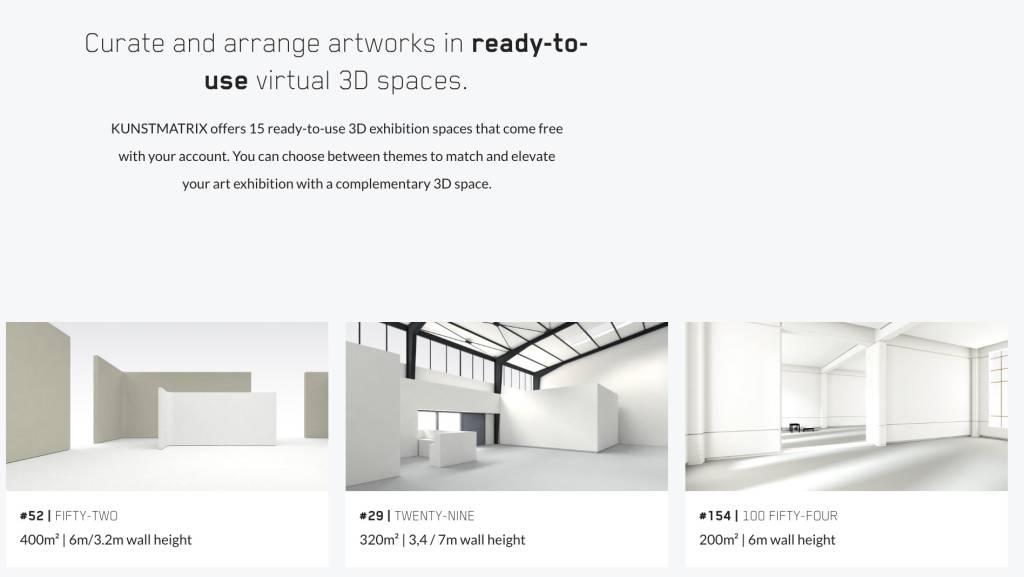

For the course exhibition, students made a selection of their works, which were discussed within the group. The final curation, as well as putting up the works and preparing them in size – was done by the course organizer, i.e. myself. The platform provided by TAMK was Kunstmatrix, where we were able to select one of the dozen or so basic gallery spaces.

Pretty soon we noticed that the “nicer” virtual gallery options in Kunstmatrix were also more expensive than the basic ones. This seemed to be one way for the platform to make some extra revenue, which of course made sense. They also charged extra for handling sales and for providing statistics such as visitor numbers. We noticed that many virtual art gallery providers work this way. They provide a service, and the content is up to the users.

Screenshot of Kunstmatrix galleries

Before the course participants uploaded their works (or scans of their works), we all wanted to know how Kunstmatrix would handle copyright issues. The course had two visiting teachers – Anna Laamanen of Kansallisgalleria and Timo Bredenberg, artist – who had both touched on online copyrights issues in their lectures. Among the FAQ’s of Kunstmatrix, we found indeed a bit of information about copyrights. However, the info was worded a little unclearly. We could not quite make out if Kunstmatrix was leaking some of its content to feed generative AI models or not. For this reason, one of the participants decided to drop out of the course and not show their works in the gallery. This was understandable.

Kunstmatrix had several videos and step-by-step instructions on how to upload the works, what sizes and format they should be, and how to place them on the virtual walls. Despite the instructions, the system still felt a bit clumsy to us, due to the many steps one had to take. Sizing of the works took some time to learn, as well as placing text on the walls and editing it. We did not have 3D scans of sculptures or any 3D modelled artworks, although it would have been possible to upload those on Kunstmatrix, too. Some artists opted to have music added to their works. When a visitor would come closer to a work, music or spoken text would start playing. (I acted as one of the speakers, as the artist said they liked my way of pronouncing English.) Kunstmatrix let us add contact info of the artist and if the work was either for sale or not, or already sold. Video works could also be uploaded in the gallery, as long as their file size was not too large.

The participants also made an exhibition poster, after we had decided on an opening date. The poster – with a horizontal and vertical version – was then spread in social media, as all of us advertised the exhibition and its opening to our friends, colleagues and other contacts.

Art exhibition openings are more often than not intensely social events. People with different roles in the fine art community come together to meet at exhibition openings: the artists themselves, the art appreciating public (including potential buyers), art curators, as well as art pedagogues. Our challenge was to establish a feeling of a real exhibition opening while having a gallery where the visitor would not see anybody else. According to one statistic that a student found, a virtual art gallery visit usually lasts 1-3 minutes or less.

Our solution was to create side channels for people to meet each other. We established a Telegram page, as well as a live Zoom room where people could hang out. Fanni Niemi-Junkola, project manager of KUVATA, came to hold a short welcome speech. About 75% of the people invited did not attend the exhibition opening, though. Still, we opened cans of beer or bottles of wine at home to celebrate the exhibition.

As one of the participants had dropped out mid-course, there was one empty wall left in the gallery, so I scanned and uploaded three of my own recent acrylic paintings and added them on the wall. Perhaps it was an unusual choice, but the other participants did not have anything against it. (The original paintings had been given as a gift to one of my sons, so they were not for sale anyway.)

I cannot estimate how many visitors we had on the KUVATA Kunstmatrix exhibition, since Kunstmatrix did not show us any statistics unless we paid them extra.

What did we learn out of this experience in the end? What I certainly recommend is to hold a virtual exhibition side by side with a physical one. Social contacts (so important in the art world) happen much more easily in a physical gallery. And unless one’s work is meant to stay in the digital world – such as NFT’s – people will want to have a chance to experience it physically. Another thing to recommend is to open and close the virtual exhibition at a set date, and not let it linger on as a depository of old works.

Certainly, digital dealership of art is important and growing, but virtual galleries are not the direction where things are going right now. For an artist willing to sell their works online and eager to get noticed by international curators, it would be prudent to take the old-fashioned route and join an artists’ association and participating their joint exhibitions.

— Carita Forsgren 2025