One of the critical issues that the EduMAP project was designed to address is the failure of the adult education (AE) system to reach out in effective ways to the most vulnerable and marginalised young adults. Whilst there are many educational opportunities identified and seized by already educated or highly educated youth and adults, oftentimes adult education fails to connect with youth with basic or no education, or in other situations of vulnerability. To bridge this gap, we have employed communicative ecologies as an approach for shedding light on both the points of encounter and the mismatches between the supply and use side of adult education as regards vulnerable youth.

What are communicative ecologies?

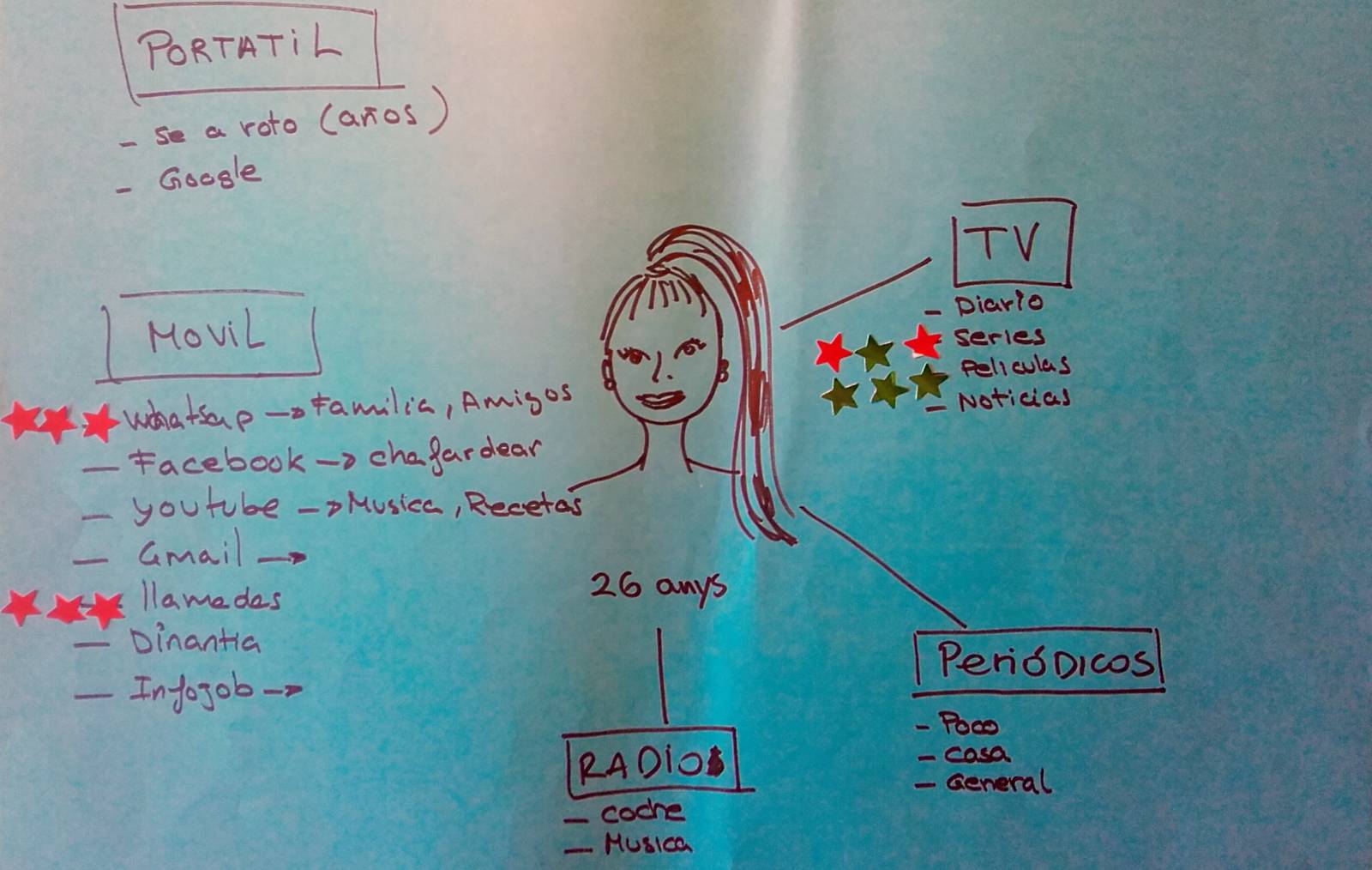

Communicative ecologies encompass the flows of information and communication in people’s lives, as well as the informational and communicational resources and social networks. As a conceptual and methodological tool, communicative ecologies enable us to map and understand how people access, produce and transmit information and how they communicate in their socio-cultural contexts, the social networks they nurture and the media they use.

Our progress thus far

We have collected data to map the communicative ecologies of the various stakeholders active in the field of adult education, particularly providers, vulnerable youth enrolled in AE courses and those who have not benefitted yet from adult education opportunities. Across 40 good practice cases of AE programmes in 20 European countries and Turkey, we have looked at how adult education providers structure their information provision and communication practices inside and outside the organisation, and how youth currently attending AE programmes are integrated or partake in these information and communication flows. Further, we have looked more closely at the communication practices of vulnerable youth in eight European countries and Turkey, who are not currently enrolled in adult education programmes, and many of whom have never attended an AE course. Through interviews, focus groups, participant observation and communicative ecologies mapping, we have examined the communication context and practices of vulnerable youth, including an overview of the channels, networks, and content they use in their everyday lives (informal level) and for work and education related purposes (formal level). Further, we have sought to understand how these communicative practices relate to their social and professional goals and aspirations.

Communicative ecologies maps of two Roma women in Catalonia, Spain

What has emerged so far?

Data collection has been finalised, and data coding and analysis are underway. Structured findings are still to be distilled, however at this stage we can share a series of very preliminary findings that emerged through discussions and sharing of notes and observations among project partners:

Firstly, diverse and localised uses of information and communication technologies, platforms and applications can be identified, often with pronounced differences across what can be called formal and informal contexts of communication. For example, mobile phones are widely used among vulnerable youth in countries such as Romania and Spain, despite scarce economic resources. The mobile phone (often a smart phone) is used to cover a variety of communication practices spanning informal purposes (being in touch with friends and family) but also looking for and discussing job opportunities. But uses can also differ greatly among formal and informal settings. For example, vulnerable youth interviewed tend to use technology differently depending on context: social media platforms such as Facebook are restricted to family and friends, and not trusted to pursue leads about educational or job opportunities. Likewise, email is considered too slow and instead, phone functions such as voice or IMS are preferred for quickly following up on leads.

Secondly and to counter the pervasiveness of technology, what emerges so far is that the human dimension in information access and communication is of fundamental importance. Youth who come to access adult education often do so based on the recommendation of other people – care takers, social care and supportive services, counsellors or acquaintances. Information passed on through people networks is considered more reliable and trustworthy than information found on the Internet. Many young people interviewed considered Internet a valuable information hub, but not so trustworthy for securing education and job opportunities, as the information source could not be identified and also the time gap between posting and viewing information was considered too wide.

The above notes are, of course, very generalised initial leads that are considerably more nuanced and elaborate in the context of young people’s lives and social, cultural and economic environments. Findings will become available in Autumn 2018, and will be used to identify alternative models and pathways by which AE policies and programmes can better respond to the educational needs of vulnerable young people, and be easier to access by youth through channels and networks that they are familiar with.

Comments