Original text reproduced from the Centre of Excellence in Game Studies

Outline

Suppose you played Mario Kart Wii (Nintendo, 2008). In that case, you probably are familiar with moving around motion-sensing controllers to steer through a multitude of tracks. However, have you ever noticed yourself or the players around you leaning into the curves and tensing up when items hit your avatar? In this post, I took a closer — but short — look into these bodily expressions, or somatic expressions, as part of a transdisciplinary approach: the application of somaesthetics.

Before taking a closer look at the specific application for research on digital play experiences, a short definition of what somaesthetics encompasses needs to be provided here. Proposed by Shusterman in the late 1990s, somaesthetics is an attempt to systemize the analysis of the body as a site for sensory experience (aisthesis) as well as for expression, transformation, and sensory improvement (Shusterman, 1999). While originally typically applied to performative analogue practices such as athletics, dance, or body modification, the discipline later finds implementation in observing the experiences of somatic interaction with technological devices and their design (Lee, Lim and Shusterman, 2014) and bodily expressed empathy in media perception (Ryynänen, 2022).

Empathetic Perception: A First Somaesthetic Framework for Gaming

While the experience of digital gaming is obviously a multisensory and multimodal one, including visual, auditive, haptic, and spatial (both within game and gaming spaces) sensory perception, one of the most accessible elements for introduction might be the visual perception of on-screen events and the understanding of digital games as somatic media. This last term, derived from Ryynänen’s concept of somatic film, describes media whose features are designed to extend the aesthetic experience into bodily reactions (Ryynänen, 2022). These include the flinching moments during jump scares, the internal contractions when witnessing gore, the tension experienced during intense scenes, or the rapid eye movements and bodily tension during fast-paced action scenes. The body of the consumer mirrors the experienced on-screen intensity. What is here recognized for the categories of horror or action in the film and the related physical effects (disgust, tension, twitching) easily translates the experience of digital gaming but is further intensified within this medium. The bodily reactions and their direct experience through the viewer’s/player’s soma both express and create an empathetic relation, an emotionalized relationship to a virtual body, described by Ryynänen for the film as “put[ting] our soul into the real-life protagonist”. While the notion of “soul” might seem to be a rather abstract concept, the interdisciplinary nature of somaesthetic frameworks here comes into play, additionally providing a link back to our introductory example of Mario Kart.

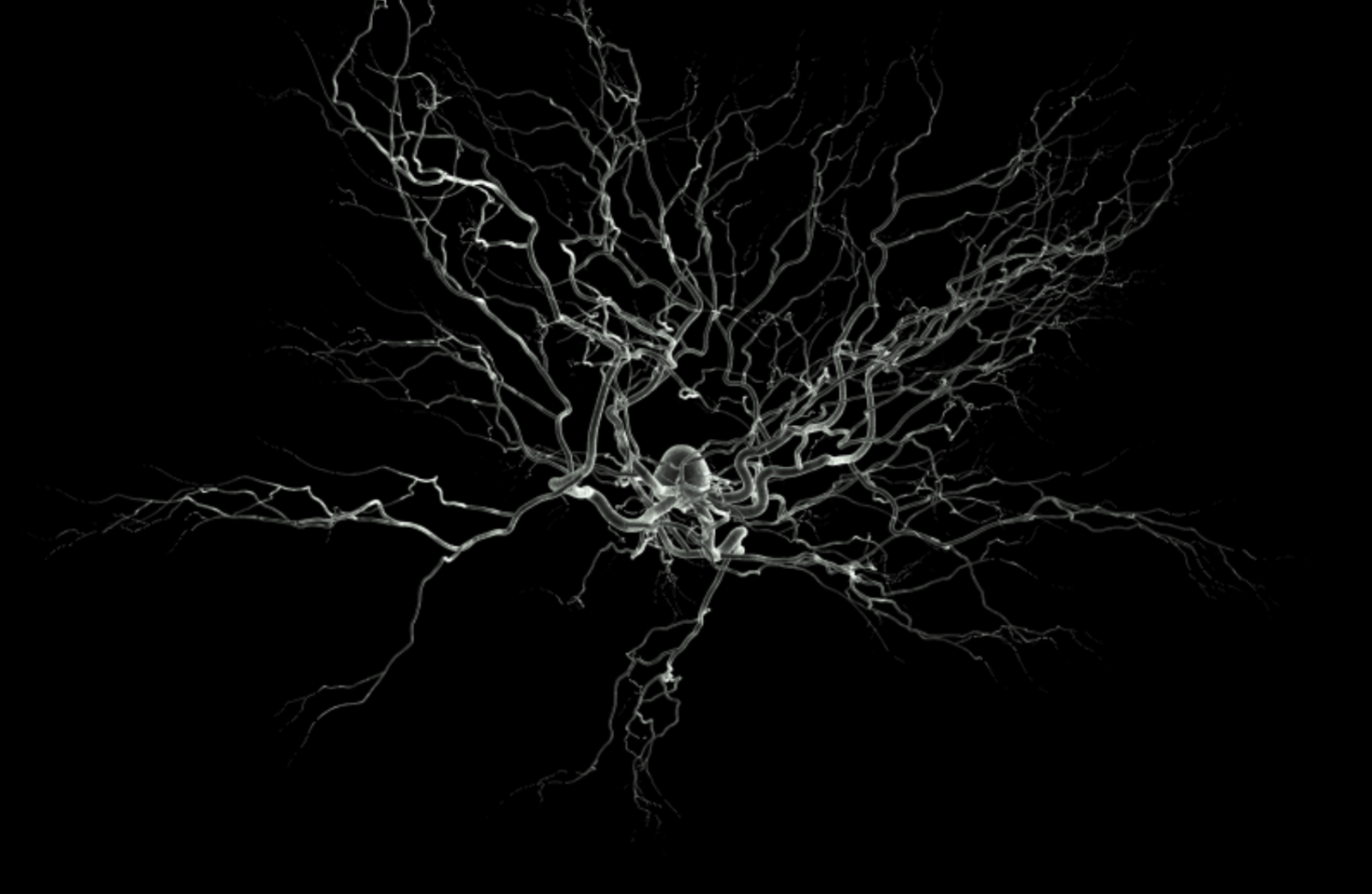

Indeed, the description of an empathetic mirroring of on-screen events through viewers’ bodies finds its origin in neuroscientific research and the presence of mirror neurons. Observing a physical action on the screen activates the viewer’s motor cortex, leading to an internally experienced and lessened reproduction of the observed action or experience (Gallese and Guerra, 2020). Physical on-screen actions here need to be understood as a broad term, not just including bodily movements (turning a wheel, firing a gun, climbing, and jumping) but also physical expressions of emotion. Besides the physical activation of the player’s body through experiencing tense racing in Mario Kart, examples of those can typically be found in horror games when witnessing the mutilation of the own avatar (disgust and discomfort, e.g. System Shock, 1994; Prey, 2017), or in the intimate and romantic scenes of RPGs and Dating Sim Games (arousal and joy, e.g. Dragon Age: Inquisition, 2017; Dream Daddy, 2017). These on-screen physical moments are potentially experienced not solely and primarily on an emotional level but first through the soma of the player, which then affects an empathetic emotional reaction. Still, it has to be emphasized that this does not imply a generalized soma but rather underlines the relevance of the individual experience, shaped by an emotional and physical condition, cultural habituation and emotional preconditions. In those moments of somatic stimulation and influenced by said preconditions, the player is individually and uniquely ‘thinking through the body’ (Ryynänen, 2022).

Outlook: From Visual to Material to Exercise

While the primary somatic effects of visual perception function as a good first introductory peak into the framework, the multisensory and multimodal nature of digital gaming experiences obviously extends further, and even more than film, athletics, or theatre involves the consideration of technological interaction and soma (Nielsen, 2010), as peripherally present in experimental Human-Computer-Interaction research and Research-through-Design practices (Belling and Buzzo, 2021).

Potential elements for further consideration include not only in-game atmospheres and their visual and auditive representation but also, as shown in the introductory example, body-movements as a reaction to on-screen events, haptics (controller types and modifications, vibrations), hardware and its modification (Lee, Lim and Shusterman, 2014), device aesthetics, and in its holistic extension even the active choice of furniture and the color of potential spatial or device lights. This holistic approach would allow for not only analyzing the act of play as a momentary somatic practice (Nielsen 2010) but also further the decision to play and the potential active preparation of a setting for it (choice of light, decorations, hardware, etc.) as an active exercise in enhancing ‘somatic sensibility’ (Lee, Lim and Shusterman, 2014).

With the current somaesthetic discourse addressing games almost exclusively in the field of athletics and interactions with technology, primarily in robotics and Human-Technology-Interaction (Belling and Buzzo, 2021), the intersection with game studies presents both a gap and opportunity, specifically when considering Extended Reality gaming, even more approximating performative bodily practice and digital play.

Author Bio and Contact

Aska Mayer (M.A.) is a Doctoral Researcher at Tampere University, working on the exploration of human augmentation in/through/as games. Within the doctoral research project, the goal is to provide a holistic and systemic perspective on augmented human bodies through the combined application of Game Studies, Somaesthetics, and HCI, as well as locating the fictional and real body as a playground for experimental bio-technological modifications.

Additional research interests include idea-historical approaches to digital games, philosophy of the neo-baroque, and apocalyptic media culture.

Lead picture copyright: Black and White Graphic of a Neural Node. Copyright (c) 2003 Nicolas P. Rougier (GNU General Public License).

References

- Arkane Austin. (2017). Prey. PlayStation 4. Rockville, Maryland: Bethesda Softworks.

- Belling, A.-S., & Buzzo, D. (2021). The Rhythm of the Robot: A Prolegomenon to Posthuman Somaesthetics. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction (TEI ’21) (Article 62, pp. 1–6). New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3430524.3442470.

- BioWare. (2014). Dragon Age: Inquisition. PlayStation 3. Redwood City, California: Electronic Arts.

- Gallese, V., & Guerra, M. (2020). The Empathic Screen: Cinema and Neuroscience. 1st ed. Oxford University Press.

- Game Grumps. (2017). Dream Daddy: A Dad Dating Simulator. Microsoft Windows. Glendale, California.

- Lee, W., Lim, Y., & Shusterman, R. (2014). Practicing Somaesthetics: Exploring its Impact on Interactive Product Design Ideation. In Proceedings of the 2014 conference on Designing interactive systems (DIS ’14: Designing Interactive Systems Conference 2014) (pp. 1055–1064). Vancouver, BC, Canada: ACM. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/2598510.2598561.

- LookingGlass Technologies. (1994). System Shock. Microsoft Windows. Austin, Texas: Origin Systems.

- Nielsen, H. (2010). The Computer Game as a Somatic Experience. Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture, 4(1), 25-40. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7557/23.6112.

- Nintendo EAD. (2008). Mario Kart Wii. Nintendo Wii. Kyoto: Nintendo.

- Ryynänen, M. (2022). Bodily Engagements with Film, Images, and Technology: Somavision. 1st ed. Routledge. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003248514.

- Shusterman, R. (1999). Somaesthetics: A Disciplinary Proposal. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 57(3), 299–313. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/432196.