ANNA-RIIKKA AARNIO

Political interest – along with satisfaction with the way democracy works – is the most significant determinant of political trust of young adults in Finland. Many other usual determinants of political trust, such as internal or external political efficacy or satisfaction with the government, are not statistically significant when examining young people. Therefore, political trust of the youth seems to form less systematically than that of adults. Furthermore, over the last decade, political trust of the youth has declined more steeply than political trust of the older population.

Political scientists have emphasized the importance of sufficient level of political trust for decades (i.e. Almond & Verba 1963, Easton 1965, Citrin 1974). Trust makes institutions work more efficiently, reduces the need for surveillance and can even lower crime rates (Listhaug & Ringdall 2008). Citizens’ trust towards decision makers, institutions and political system is the key to their legitimacy. A common definition of political trust is how well political actors respond to citizens’ normative expectations (i.e. Miller 1974, Hetherington 1998). Regardless of the positive effects of high level of political trust, scientists underline the importance of critical citizenship rather than absolute “blind” trust (Norris 2011, Van der Meer & Zmerli 2017).

Considering the need for critical voices in societies, low level of political trust itself is not too dangerous. In many cases, distrust or at least critical attitude towards political actors is justified. Low level of trust becomes alarming when distrust is deep and widely spread or linked with wider political alienation. Especially concerning is a situation in which low trust is associated with particular social groups (Borg & Kestilä-Kekkonen 2017).

Young people and their political attachment has been a popular topic of discussion. However, a lot more attention has been paid to adolescents’ political interest, participation, and knowledge than to their trust in politics (i.e. Fer 2013, Rapeli & Borg 2016). This brief blog post is based on the writer’s recent master’s thesis on political trust of the 18–29-year-old Finns. The data come from the Finnish National Election Study (FNES) and the European Social Survey (ESS).

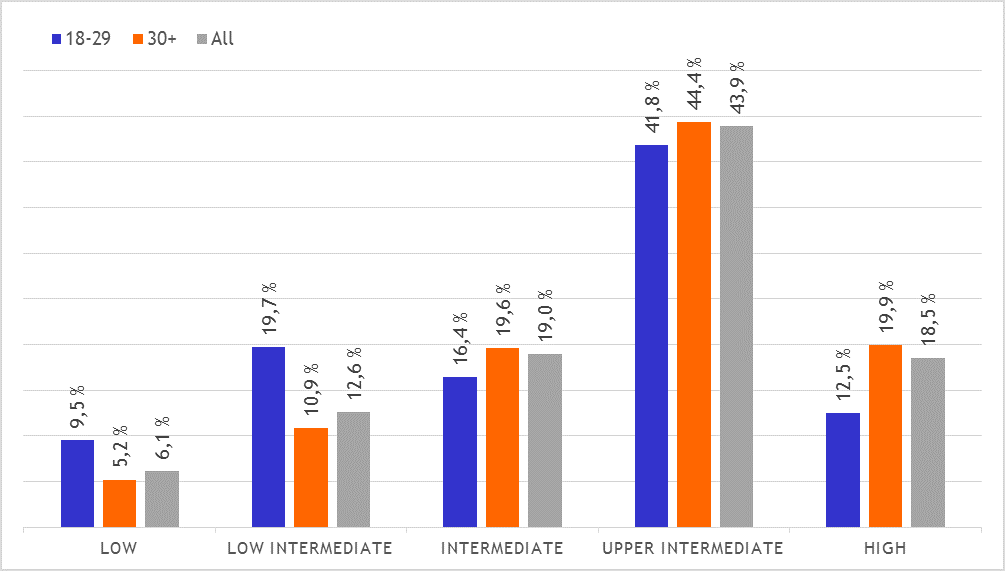

Figure 1 shows the differences in political trust between the young and the older generations based on the FNES data in the year 2015. The table shows that political trust is relatively high in both groups: 54 percent of the younger and 64 percent of the older Finns have upper intermediate or high political trust. Yet, lower level of political trust is more common among the young people. Approximately 30 percent of the young respondents have either “low” or “low intermediate” political trust, while the share of the older respondents in the corresponding categories is roughly half of that.

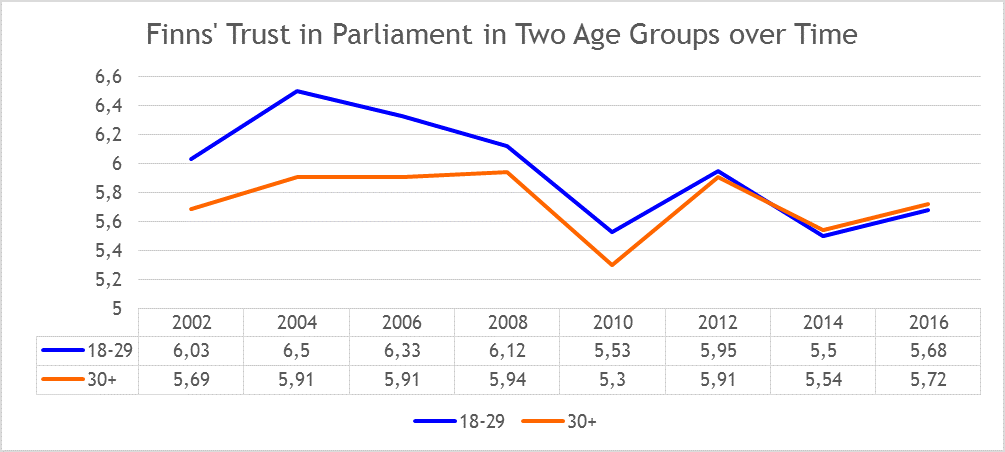

ESS data shows that the level of political trust (measured as trust in parliament) has declined more steeply among the young adults than among the older generations. While in the beginning of 2000s the average level of political trust of the young Finns was clearly higher, in ten years it has declined to the same level if not lower in comparison to the older population.

Regression analyses show that – as is the case with adults – the key variables explaining political trust of the youth by explanatory power are political attachment and institutional performance. Political interest is an example of the previous as well as are other determinants that measure people’s attachment to the political system. Institutional variables on the other hand measure the responsiveness of the system, for example in terms of economic performance. However, other variables that explain political trust of adults, like internal or external efficacy, were not statistically significant in terms of the young people. Whether this is a temporary phase in a life cycle or a more stable characteristic to this particular age cohort, stays unsolved, although, most likely both explanations have some effect (Wass 2007). Political interest stands out as the most important single determinant of political trust of the youth alongside with satisfaction with the way democracy works.

One of the main conclusions is that, rather than being worried about the declining or low levels of young adults’ political trust, we should concentrate on making politics more appealing to young people. Different dimensions of political attachment are intertwined, but with great probability, interest in politics is the key to wider attachment in politics.

Results are available in more detail in Finnish at http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:uta-201710112597.

Anna-Riikka Aarnio is a recent graduate in political science at University of Tampere and now works at Statistics Finland’s Data Collection Department. She has previously worked as a research assistant in CONTRE.

References

Aarnio, Anna-Riikka (2017), Miten luottamus rakentuu? Tutkimus suomalaisten nuorten poliittisesta luottamuksesta. Master’s thesis. [http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:uta-201710112597].

Almond, Gabriel & Sidney Verba (1963), The civic culture: Political attitudes and democracy in five nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Borg, Sami & Elina Kestilä-Kekkonen (2017), “Viisi väitettä osallistumisesta”. In Kestilä-Kekkonen, Elina & Paul-Erik Korvela (eds.), Poliittinen osallistuminen – Vanhan ja uuden osallistumisen jännitteitä: 52–75. SoPhi 135. Jyväskylä: SoPhi.

Citrin, Jack (1974), “Comment: The political relevance of trust in government”, The American Political Science Review 68(3): 973–988.

Easton, David (1965), A systems analysis of political life. New York: Wiley.

Fer, Simona (2013), “Young people’s trends in political trust and views of their declining sense of duty”, Journal of Identity and Migration Studies 7(1): 111–132.

Hetherington, Marc (1998), ”The political relevance of political trust”. The American Political Science Review 92(4): 791–808.

Listhaug, Ola & Kristen Ringdal (2008), “Trust in political institutions”. In Ervasti, Heikki, Torben Fridberg, Mikael Hjerm & Kristen Ringdal (eds.), Nordic social attitudes in a European perspective: 131–151. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Miller, Arthur (1974), “Rejoinder to ‘Comment’ by Jack Citrin: Political discontent or ritualism?”, The American Political Science Review 68(3): 989–1001.

Norris, Pippa (2011), Democratic deficit: Critical citizens revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rapeli, Lauri & Sami Borg (2016), “Kiinnostavaa mutta monimutkaista: Tiedot, osallistuminen ja suhtautuminen vaikuttamiseen”. In Grönlund, Kimmo & Hanna Wass (eds.), Poliittisen osallistumisen eriytyminen. Eduskuntavaalitutkimus 2015: 379–397.

Van der Meer, Tom & Sonja Zmerli (2017), ”The deeply rooted concern with political trust”. In Zmerli, Sonja & Tom van der Meer (eds.), Handbook on political trust: 1–16. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Wass, Hanna (2007), ”The effects of age, generation and period on turnout in Finland 1975–2003”, Electoral Studies 26(3): 648–659.

Comments