THOMAS KARV

It is not hard to see that the referendum was framed as a battle between the heart and the head. Since the Brexit-side could not win the battle of the heads, it went all in for the battle of the hearts.

On the 23th of January, 2013, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (UK) David Cameron declared in his now famous “EU speech” that if he and the Tories were re-elected in the general election of 2015, he would demand a re-negotiation of the terms between the UK and the European Union (EU).

However, Cameron also promised that after the re-negotiation of the terms he would announce a referendum to let the British citizens have the last say regarding the UK´s future EU-membership.

Cameron made this decision, presumably, as a tactical move to both silence the more Eurosceptic voices of his own party and to counteract the growing popularity of the openly Eurosceptic United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP).

It is possible that he also sincerely believed that he would be able to negotiate better terms for the UK, and that his case for the UK to remain part of the EU could be explained to the British citizens by using rational economic arguments. It is, however, now obvious that he made an enormous mistake.

Plenty has been said about the Brexit referendum, but much more is yet to be said about the actual implications of the outcome. The citizens of the UK voted in a small, but decisive, majority of 51.9 – 48.1 of leaving the EU.

Although the referendum was officially only an advisory referendum, and therefore not legally binding, Cameron and his governing Tories had prior to the referendum promised that they would proceed according to the outcome – a promise that they still, at least officially, stand by.

As we know, Cameron himself resigned immediately as it became clear what the outcome would be. The new Prime Minister will most likely be one of the leading figures of the Brexit campaign, the former Mayor of London, Boris Johnson.

Article 50 in the Treaty of the European Union made it officially possible for a state to leave the European Union unanimously: “Any Member State may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements” (Article 50.1). For the United Kingdom to officially leave the EU, its government will first have to officially notify the European Council of its intentions and negotiate the terms of withdrawal.

If the EU and United Kingdom fail to reach an agreement on the terms of withdrawal, all of the earlier treaties will cease to be legally binding on the UK two years after that they have officially notified the European Council of their decision. This process will most likely not start until a new British Prime Minister is chosen in October. Before that happens, we can only speculate about separation and the actual consequences for the rest of the EU and for the UK.

From a political scientists’ point of view, there are many different ways to explain the outcome of the Brexit referendum. As the referendum showed, there was undoubtedly a lack of citizen support for the EU in the UK.

The concept of support is important, because it is assumed to provide a political regime with political legitimacy. As an increasingly politicized union, the EU and its legitimacy are dependent on the approval of the EU-citizens.

According to David Easton (1965), the concept of support should be divided into two interrelated but theoretically separable levels of support, specific (utilitarian) and diffuse (affective). At the aggregate level specific support touches on the more observable levels of support and is assumed to function quite rationally: A supports B because A benefits from supporting B. Diffuse support on the other hand indicates more deep held loyalties and does not change solely according to performance. It is also much harder to create.

Indicators of specific support are often operationalized to measure the level of support for the EU, because the EU has not yet managed to create any deeper held loyalties towards it, despite many efforts. However, at the level of specific support, the Remain-side undoubtedly failed in enlightening the British citizens on why it would have been rational to support a continued EU-membership, even though almost all of the major economic think thanks and institutions had stated that it was better for the British economy to remain in the EU.

In November 2012, two months before Cameron made his referendum announcement, UK-trust in the EU was the second lowest in the EU, only topped by Greece.

Simultaneously as the European Union has transformed from a mainly economic community into a semi-political union, the opposition towards this development has grown, especially as the EU has not managed to deliver all of the promises of economic prosperity and stability.

For the federalists, the cure for the poor performance has always been more and deeper European integration, while Eurosceptics have been promoting a cease, or even reversal, of integration.

Considering these circumstances, it is not hard to see that the referendum was framed as a battle between the heart and the head. Since the Brexit-side could not win the battle of the heads, it went all in for the battle of the hearts.

When the British citizens where asked to vote, the two alternatives were therefore also logically framed as: “Vote leave, take back control of our sovereignty and economy from the EU bureaucrats!” or “Vote remain, even though we don´t like it we still benefit heavily from it”.

David Cameron would have been wise to actually make sure that the majority of the UK citizenry was aware of the benefits of EU membership before he announced the referendum. Political trust, as an indicator of specific support and regime performance, is one of the indicators that Cameron should have researched. Maybe he would, then, have changed his mind about his gamble.

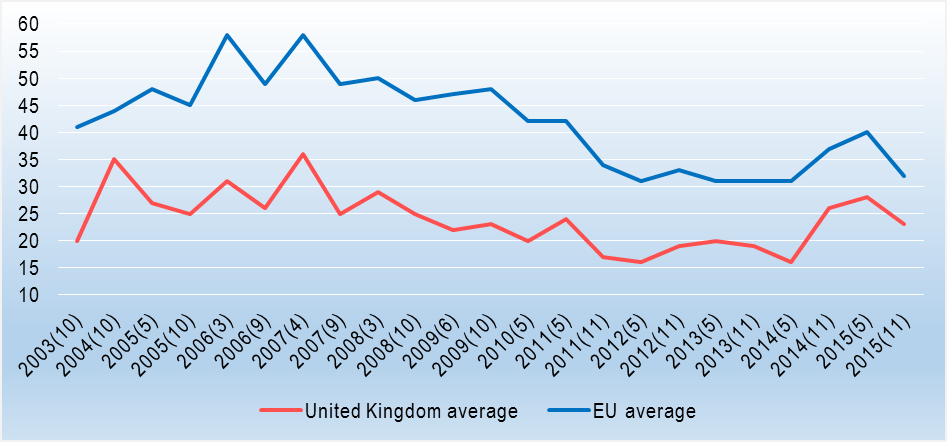

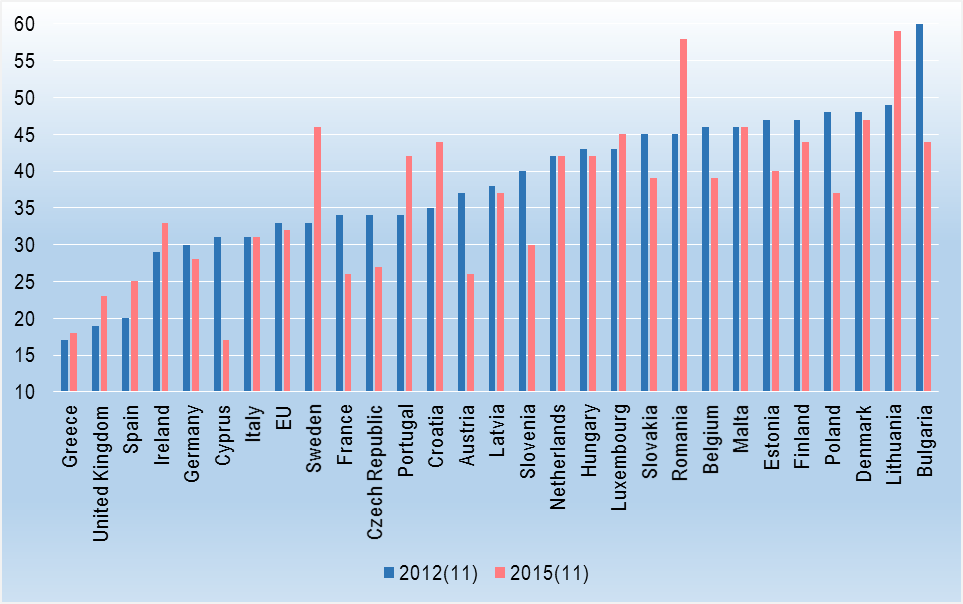

Since 2003, the aggregate level of trust in the EU within the UK has been much under the EU-average (table 1). In November 2012, two months before Cameron made his referendum announcement, UK-trust in the EU was the second lowest in the EU, only topped by Greece (see table 2). Three years later, the trust of UK citizens in the EU was still the third lowest of all member countries.

Levels of trust in the EU are of course just one of many indicators when trying to explain the outcome of the Brexit referendum, but the low levels of trust in the EU within the UK clearly illustrate what was a huge risk Cameron took when setting out to call this referendum. It is hard to vote for someone or something you do not trust. As a result, a new and undoubtedly more unstable Europe has been created.

References:

Easton, David (1965): A systems analysis of political life. New York: Wiley.

European Commission (2003-2015): Eurobarometer data. INRA, Brussels. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne.

MSSc Thomas Karv is a PhD student at Åbo Akademi University in Vaasa and part of the Consortium of Trust Research (CONTRE) group. His main research interests lie in the fields of political attitudes, the European Union and European integration.

Hello,

thank you for this commentary.

I would like to use it for my blog, as a resource. Of course with credits given. Would you mind?

Yours

Peter

Peter Ondrovic

30.6.2016 16:49

Hi Peter,

Sure, go ahead!

Best,

CONTRE-team

Josefina Sipinen

1.7.2016 09:30