THOMAS KARV

There is only one year ahead of us before the EU citizens will again have the opportunity to elect their national representatives to the world’s only directly elected supranational political chamber, the European Parliament (EP). This will be the ninth EP-election, but post-Brexit the number of MEPs elected will drop from 751 to 705. The election takes place during May 23–26, 2019 and the outcome will affect the direction of the EU for the following five years.

Even though the power of the EP has increased over time, the EP-election is still widely considered as a “second-order election”[1] and the EP’s real decision-making power is still very limited.[2] The turnout in EP-elections has also been declining for every election, which for some indicates that there is a democratic deficit at the European level threatening the EU´s democratic legitimacy.[3]

Scholars agree – at least to some extent – that the levels of trust in the EP are associated with the levels of trust in the national parliaments. As the EU citizens do not have enough knowledge about the workings of the EU, the quality and performance of the national level political institutions functions as a proxy when attitudes towards the EU are formed.[4] This relationship, however, is not straightforward.

As always with attitudes towards the EU, there are significant cross-country variations within the EU-28 that are changing over time. Within the context of trust in the EP, there are two hypotheses about how the levels of trust in the national parliaments affect the levels of trust in the EP.

According to the compensation hypothesis, trust in the EP is derived from a lack of trust in the national parliament, meaning that trust in the EP compensates for a dysfunctional national parliament. However, the association also works the other way around: higher levels of trust in the national parliaments might predict lower levels of trust in the EP.

The compensation hypothesis has been the prevailing explanation of why the levels of trust in the EP were, on average, higher in the post-communist Member States during the mid-2000s than in the older Member States. In the post-communist Member States the EU and the EP specifically have symbolized an institutional reference point during the democratic transition-period. However, in the older Member States the levels of trust in the national parliaments have generally been on a higher level, and hence the EP has been met with more suspicion by the public within the older Member States.

According to the congruence hypothesis, attitudes towards the national parliament transfer into similar attitudes towards the EP. This means that if an individual tends to trust the national parliament, it is likely that the same individual also trusts the EP. Following the same logic, if an individual’s trust towards the national parliament is low, it is very likely that his or her trust towards the EP is also low. This creates congruence in attitudes towards institutions at different levels, which could be described as an “institutional trust syndrome”, meaning that trust at the national level spills over to the European level.[5]

The developments in trust in the EP and in the national parliaments during the last ten years seem to provide support for the congruence hypothesis: at the individual level, association between trust in the EP and trust in the national parliament have become stronger over time in most of the Member States.

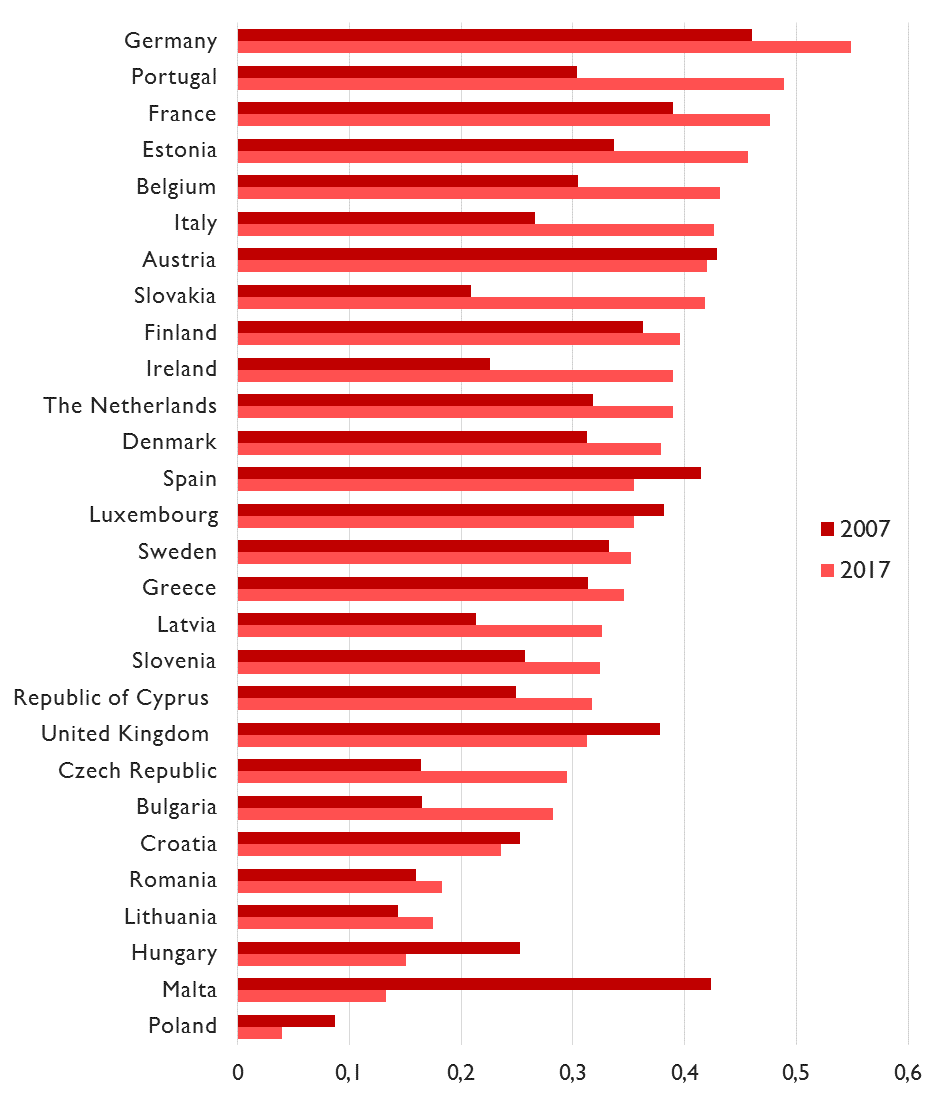

The Eurobarometer (EB)[6] data produces interesting results regarding the development of trust in the national parliament and trust in the EP[7] within the Member States between two time-points, 2007 and 2017. The results of Pearson’s R correlation analysis are illustrated in Figure 1.[8]

The correlation between trust in the national parliament and trust in the EP has become stronger in 20 out of 28 Member States. In Germany and France, the correlation is strongest, while it is weak or non-existent in countries such as Poland and Hungary. In Poland, there is currently no statistical relationship between trust in the EP and trust in the national parliament. The trends in Hungary and Poland contradict the EU-28 average trend, which shows that there has been a steady rise in the association between trust in the two institutions, indicating that the EU citizens in general are more and more prone not to differentiate between institutions at the national and European level.

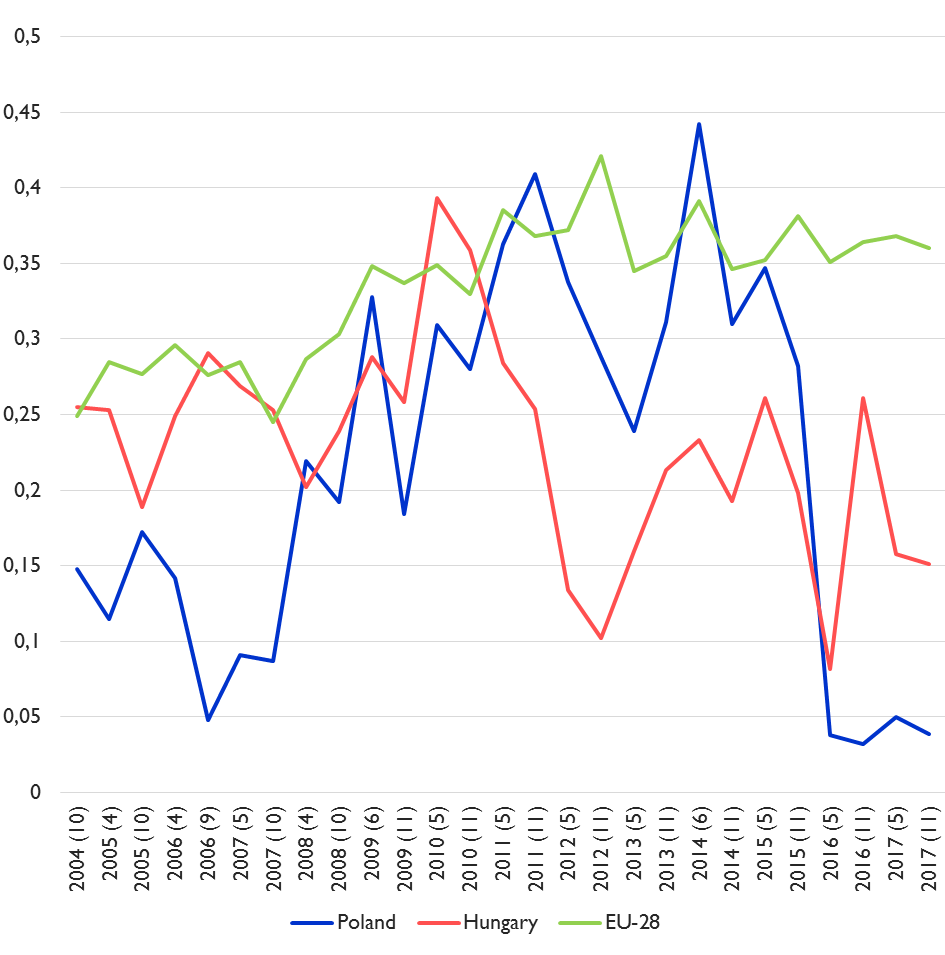

As Figure 2 demonstrates, there is a divergent trend within these two countries that started in 2010–2011, but that has since 2014–2015 become even more apparent. What might explain this?

Both Poland and Hungary have been widely criticized by the EP for implementing policies, which are deemed illegal by the EU-law. Simultaneously and perhaps ironically, the same countries are among the biggest net beneficiaries of EU money.

The governing party in Poland, Law and Justice (PiS), and the governing party of Hungary, Fidesz, have both been promoting nationalistic and protectionist policies, which seem to have had a polarizing effect on their respective electorates. In addition, governments in both countries have adopted the old political tactic of blaming Brussels on unpopular policies and not acknowledging the positive aspects of being a member of the EU.

While the trends in Poland and Hungary contradict the general developments in public opinion within the EU-area, it can be concluded that the EU citizens in a majority of the Member States have become less prone to differentiate when asked to evaluate the institutions at the national and European level.

This means that, indeed, one can talk about a “institutional trust syndrome” also when discussing trust in the EP and trust in the national parliaments and not only in relation to trust in different national level institutions (e.g. if one tends to trust the parliament one also tends to trust the government).

The anti-establishment wave seems to continue in Europe as the populist Five Star Movement (M5S) recently won the Italian election. Anti-establishment political movements are characterized by opposition to the political elites and distrust in the old-way of doing politics, and the development in increasing multilevel congruence of political trust indicates that more and more EU citizens seems to trust or distrust all politics instead of just national or European level politics.

MSSc Thomas Karv is a PhD student at Åbo Akademi University in Vaasa and part of the Consortium of Trust Research (CONTRE) group. His main research interests lie in the fields of political attitudes, the European Union and European integration.

NOTES

[1] Reif & Schmitt 1980.

[2] Schnidt 2015

[3] Hix & Hoyland 2013

[4] Anderson 1998

[5] Kritzinger 2003; Munoz et al. 2011

[6] Eurobarometer monitors the development in public opinion within the EU area on behalf of the European Commission. The survey-data is collected through interviews conducted twice a year and the results are presented in the Standard Eurobarometer-series. The N ranges from 500 in the smaller member states (Malta, Luxembourg) to 1500 in Germany, but in most member states there are 1000 respondents per survey.

[7] The exact words used in the question are: ”I would like to ask you a question concerning how much trust you have in certain institutions. For each of the following institutions, tell me whether you tend to trust it, tend not trust it”.

[8] The correlation coefficients range between -1 and +1. Zero indicates no association, -1 perfect negativeassociation and +1 a perfect positive association. The rule of thumb is that a coefficient of 0.1 is regarded as a weak association, 0.3 as a medium association and over 0.5 as a strong association (Blaikie 2003, 111)

References

Anderson, C. 1998. “When in doubt, use proxies: Attitudes toward domestic politics and support for European integration”, Comparative Political Studies 31: 569-601.

Blaikie, N. 2003. Analyzing quantitative data: From description to explanation. Sage Publications: London.

Hix, S. & Hoyland, B. 2013. “Empowerment of the European Parliament”, Annual review of political science 16: 171–189.

Kritzinger, S. 2003. “The influence of the nation-state on individual support for the European Union”, European Union Politics 4: 219-241.

Munoz, J., Torcal, M. & Bonet, E. 2011. “Institutional trust and multilevel government in the European Union: Congruence or compensation?”, European Union Politics 12: 551-574

Reif, K. & Schmitt, H. 1980. “Nine second-order national elections – a conceptual framework for the analysis of European elections results”, European Journal of Political Research 8: 3–44.

Schmidt, V. 2015. “The eurozone´s crisis of democratic legitimacy: Can the EU rebuild public trust and support for European economic integration?” Fellowship Initiative 2014 – 2015, discussion paper 015.

Comments