THOMAS KARV

The sudden rise and electoral success of Emmanuel Macron and his political movement En Marche! has taken France, and especially Europe, by surprise. How could it be that the supposedly eurosceptic French electorate decided, with an overwhelmingly majority, to elect a president that has been described as both a “Europhile” and a “Euro-Federalist” while simultaneously also granting his movement a majority in the parliament?

Before the start of the French presidential campaigns in the autumn of 2016 very few outside France had heard about Emmanuel Macron. Those who had, probably only knew that Macron had been a former Minister of Economy and Finance in Manuel Valls’ socialist government (2014–2016) but that he had resigned from his post in August 2016 to start his presidential campaign. However, the preparations for his successful presidential campaign were launched already in the spring of 2016 when he founded his own political grass root-movement, En Marche!

Macron has described En Marche! to be neither left nor right, but to have a very strong pro-European approach. Macron has called for reforming the Eurozone, for instance, by promoting a common Eurozone budget, supporting the introduction of a Eurozone Finance Minister, as well as advocating for more funds to the EU´s border management agency Frontex. At the same time he has been very outspoken regarding the implementation of hard sanctions against Poland and Hungary for not following EU-rules.

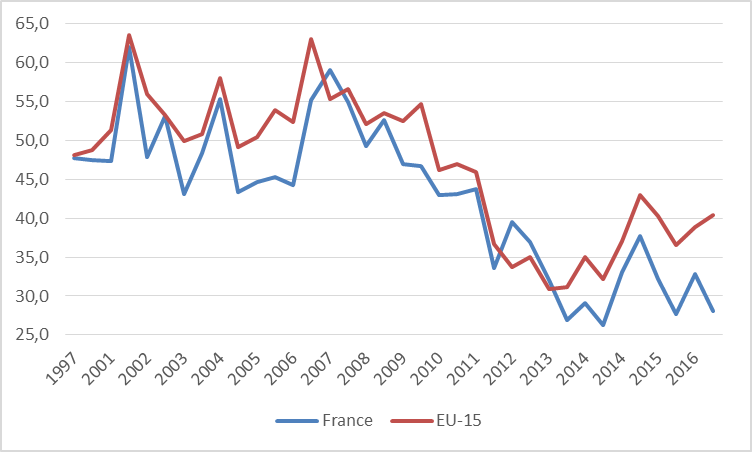

To campaign on “more Europe” in a country where Euroscepticism has been high, and public support for the EU has been steadily declining, was no small gamble. For instance, in the European Parliament elections back in 2014, the very Eurosceptic Front National became the biggest party with 24.9 percent of the votes. In addition, the average levels of public trust in the EU have in France been more or less steadily declining during the last ten years. In 2007, 55.4 percent of the French electorate tended to trust the EU, while, according to the latest Eurobarometer from November 2016, only 28.1 percent of the electorate claimed to trust the EU (see Figure 1).

Considering that European integration scholars commonly use the public´s trust in the EU as a measurement of the EU citizens approval of the workings of the EU, very few thought that it would be possible to win a French presidential election with such a pro-European agenda as Macron had. Rather, in the aftermath of the success of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump in the US presidential election, and with the success of Jeremy Corbyn in the recent UK parliamentary elections, “anti-establishment” politics seems to be the current buzzword.

As a self-proclaimed political centrist, Macron was anything but an anti-establishment candidate. Instead, he is a former private banker at Rotschild & Cie Banque, and a former minister in a very unpopular government. He is also very positive about the free-market and immigration, yet simultaneously he has anti-trade union position at the domestic level. It was very hard to predict the success of Macron and En Marche!

When Macron got 24.1 percent of the votes in the first round of the presidential election on the 24th of April, leaving behind the two anti-establishment candidates Jean Luc Mechelon from far left (19.6 %) and Marine Le Pen from far right (21.3 %), and also the scandal burdened mainstream conservative candidate Francois Fillon (20.1 %), Macron secured his place in the second round. Macron thereafter secured his presidency on the 7th of May by winning 66.1 percent of the votes in the second round in a standoff against the anti-EU candidate Marine Le Pen (Front National).

The success of Macron and En Marche! continued in the French parliamentary elections when En Marche got 28.2 percent of the votes in the first round, and 43.1 percent of the votes in the second round, providing En Marche with 308 of the 577 mandates in the French Parliament.

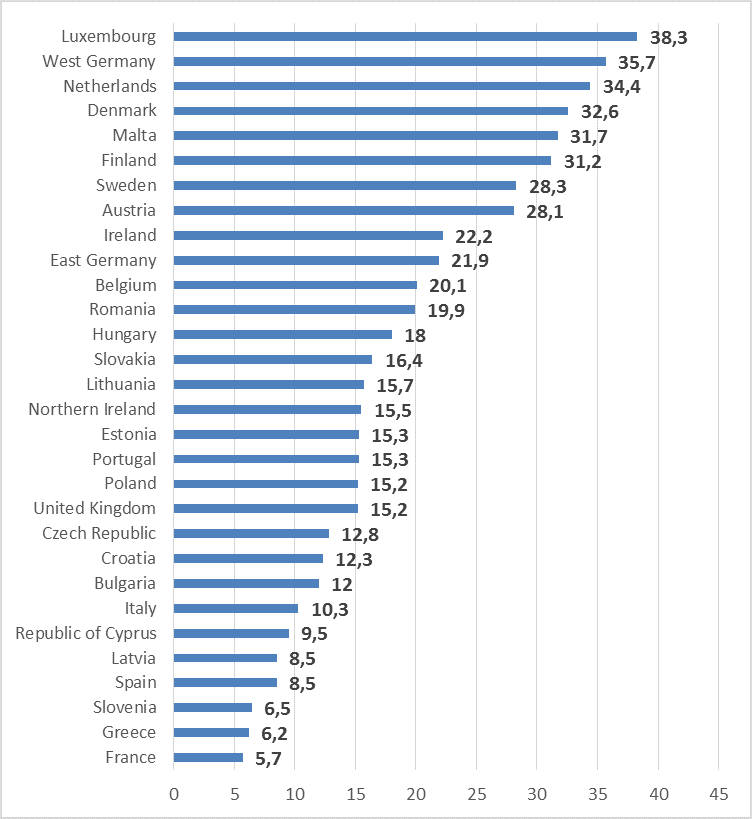

Based on the extremely low levels of trust in political parties in France, it should not have come as such a big surprise that the most popular candidates represented anti-establishment political movements (Mechelon, Le Pen) and a new centrist political movement (Macron). Compared to the whole EU-area, national levels of public trust in the political parties was the lowest in France just before the time of these elections (Figure 2).

In conclusion, it is safe to say that Macron would most certainly never had won the presidential election had he been the presidential candidate for his former party, the Socialist Party. The Socialist Party’s candidate in the presidential elections, Benoit Hamon, in the end only got 6.4 percent of the votes.

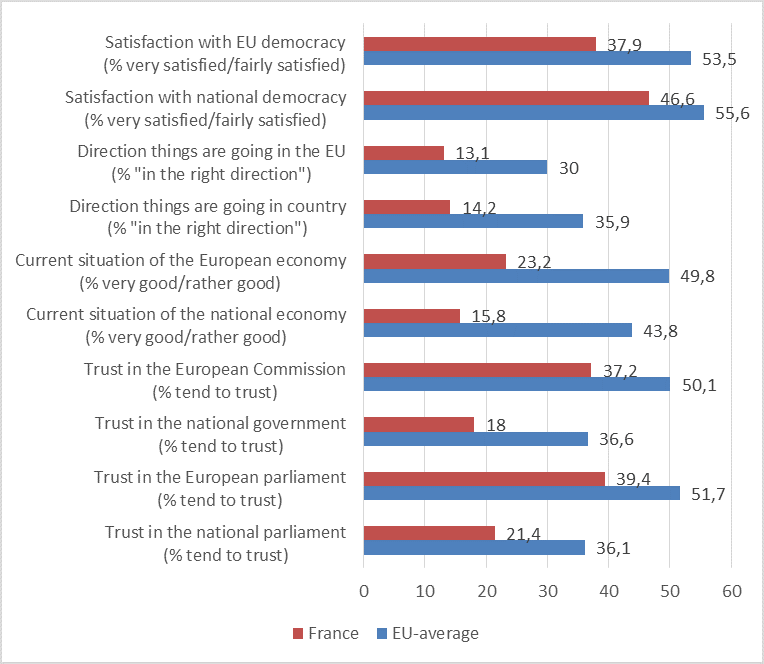

It seems that the French electorate was far from satisfied with the current state of affairs in France before the presidential election. In November 2016, only 14.2 percent of the respondents in the Eurobarometer thought that France was going in the right direction, and only 15.8 percent considered the economic situation in France “very good” or “rather good”. At the same time, the French respondents stated that they trust the European Parliament more than their national parliament, and the European Commission more than their own government (Figure 3).

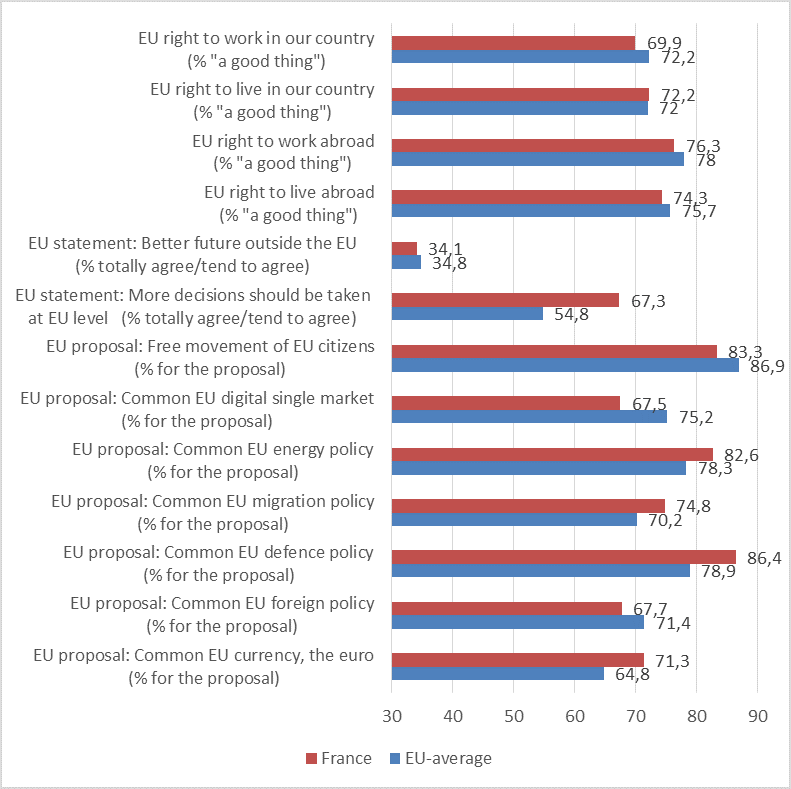

Even though the French electorate did not particularly trust the EU and the EU´s political institutions, there was still an overwhelming majority in favour of many of the EU´s integration policies (Figure 4).

For instance, 83.3 percent of the respondents were in favour of the free movement of EU citizens, 67.7 percent in favour of a common EU foreign policy, 71.3 percent in favour of the Euro, 86.4 percent in favour of a common EU defence policy, and 67.3 percent agreed with the statement that more decisions should be taken at the EU-level. Only 34.1 percent of the respondents agreed with the statement that the future would be better outside the EU.

When the future of the EU and European integration became a politicized issue in the presidential election, there was for Macron more to gain by being pro-EU than anti-EU. Especially, when there was a standoff between two candidates representing the opposite visions for the future of the EU.

The French electorate has granted Macron a mandate to implement his policies both domestically and internationally, and there are great expectations for him to become a new European strongman. Should Angela Merkel (CDU) get her mandate renewed for the fourth time in the upcoming German parliamentary elections in September 2017, or the other main and even more pro-European candidate Martin Schulz (SPD) manage to pull off a great upset (based on the most recent polling), the two most powerful remaining member states of the EU would have pro-EU leaders with fresh mandates to implement deeper European integration policies. This will have probably have remarkable implications for the future of the EU, as the European integration project will again start picking up steam after ten years of almost constant crisis.

MSSc Thomas Karv is a PhD student at Åbo Akademi University in Vaasa and part of the Consortium of Trust Research (CONTRE) group. His main research interests lie in the fields of political attitudes, the European Union and European integration.

Notes

[1] “I would like to ask you a question about how much trust you have in certain institutions. For each of the following institutions, please tell me if you tend to trust it or tend not to trust it?”

[2] “On the whole are you very satisfied, fairly satisfied, not very satisfied or not at all satisfied with the way democracy works in (OUR COUNTRY / the EU)?

[3] “How would you judge the current situation in each of the following?”

[4] “At the present time would you say that, in general, things are going in the right direction or in the wrong direction, in…?”

[5] “Please tell me for each of the following statements, whether you tend to agree or tend to disagree: More decisions should be taken at EU level”.

[6] “What is your opinion of each of the following statements? Please tell me for each statement, whether you are for it or against it?”

[7] “For each of the following statements, please tell me if you think that it is a good thing, a bad thing or neither a good or a bad thing.”

Comments