The connections between filmmaking, spaces of justice and feminist epistemologies were explored at a seven-day art-research workshop “Politics of Sexuality and Gender” organized by the Kone foundation funded research project Making Spaces of Justice Across the East-West Divide at the University of Tampere. The workshop was also a site to experiment with filmmaking as a university pedagogical method.

Cinema as a space of justice

Before coming to class, the students had been assigned a set of pre-readings: a pile of academic articles dealing with the politics of gender and sexuality. They had also written short learning diaries based on the readings.

One of the tasks we gave the students during the workshop was to transform their written learning diaries into short films. At the end of the workshop, we organized a film screening where a set of rhythmical cinematic celebrations made by engaged and liberated spirits was viewed.

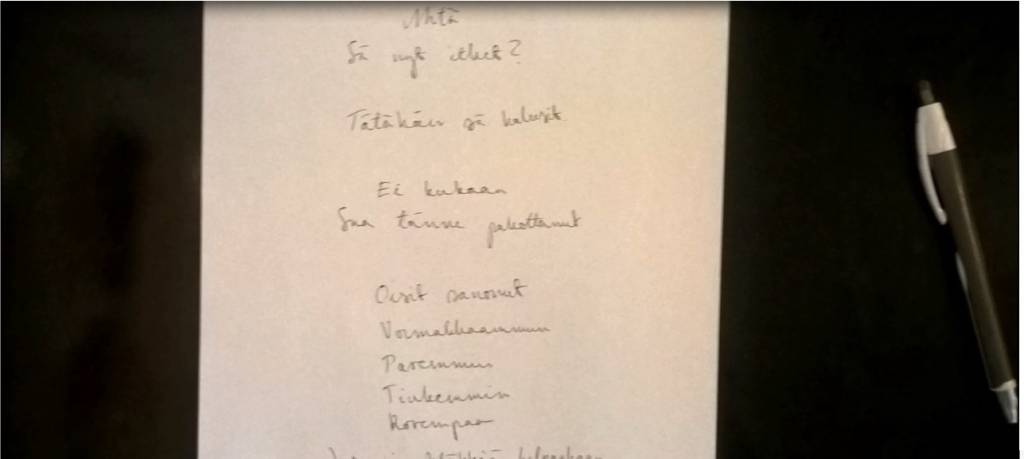

One of the films juxtaposed the idea of Finland as one of the most gender egalitarian societies in the world with experiences of sexual violence that the author and her friends had experienced. These experiences were inserted into the film in the form of notes from diaries.

One of the films juxtaposed the idea of Finland as one of the most gender egalitarian societies in the world with experiences of sexual violence that the author and her friends had experienced. These experiences were inserted into the film in the form of notes from diaries.

As most students did not have previous experience of filmmaking, reaching this point required overcoming a degree of techno-shyness and fear of equipment — i.e. learning to trust oneself and one’s own powers as a cultural producer.

To enable this, a brief introduction into video production and the basics of film language was given to the students. This equipped the students with a variety of possible tools and strategies that they could use to visualize their ideas.

We also discussed the concept of “shot”, framing and composition, camera angles and movement, mise-en-scène and editing.

“Queering Time” combined Dziga Vertov’s film material with an old Hollywood film. The point was to re-read old video clips so as to queer time, i.e. to make visible queer relationships across time as well as through space.

“Queering Time” combined Dziga Vertov’s film material with an old Hollywood film. The point was to re-read old video clips so as to queer time, i.e. to make visible queer relationships across time as well as through space.

Concrete exercises also allowed the workshop participants to dive into the terrain of “high cinema”, which many had previously seen as something exclusive and elitist. Such misconceptions about the camera and filmmaking risk overshadowing the real democratic qualities of filmmaking and the idea of cinema as a space of justice.

Film, feminism and objectivity

As the students were themselves engaged in film-making, we were better able to think through the kinds of optical illusions that the camera creates. We discussed the fact that a camera can be thought to embody the feminist methodological notions of gaze, persistence of vision and optical illusions as described by Donna Haraway.

Haraway and other feminists have problematized the assumption of value-free knowledge, universality, detachment and traditional objectivity. What we know and how we know it depends on our position in social structures, i.e. how we are situated in relation to the axes of power, gender, sexuality, ‘race’, ethnicity and class.

Filmmaking exercises also allowed the students to see in practice the connections between research and art practices. They concretized the fact that knowledge is not an object “out there” to be revealed. Rather, it is produced by an embodied author.

From objectivity to situated knowledges

Haraway uses the powerful metaphors of vision and gaze to bring in an image of an embodied, actively seeing eye. She discusses the notion of “situated knowledges” to criticize traditional notions of objectivity. The notion of “optical illusion” problematizes the possibility of dispassionate knowledge from nowhere.

While making and screening the students’ films, we discussed how these epistemological notions and the assumption of filmmaker as a cultural producer with experiences and perspectives deprived from objectivity and apolitical postures come alive in filmmaking.

The film “Superwomen” was a powerful depiction of the role that friendship and trust play in the practices through which we all engage in politics of gender and sexuality on a daily basis.

The film “Superwomen” was a powerful depiction of the role that friendship and trust play in the practices through which we all engage in politics of gender and sexuality on a daily basis.

We reflected on how this is seen in the ‘gaze’ of the camera directed by hand at the researched realities – and the researchers themselves. Or in the editing and montage techniques, forms of presentation – a screening, gallery installation, on-line streaming – and the production value of an audio-visual product.

Practical filmmaking and the concept of situated knowledges are thus related. Both problematize the assumption of an all-seeing scientific gaze as an omnipotent observer from everywhere and nowhere.

Teaching filmmaking to university students turned out to be a powerful pedagogical tool to illustrate how what we see and what we know depends, quite literally, on our location.

The camera became a metaphor illustrating how the vision of a researcher – exactly like a camera – is always positioned, and how film-makers – exactly like researchers – always choose and offer a perspective, deciding to leave things outside the frame.

Written by Daria Krivonos, Masha Godovannaya and Anni Kangas

Comments