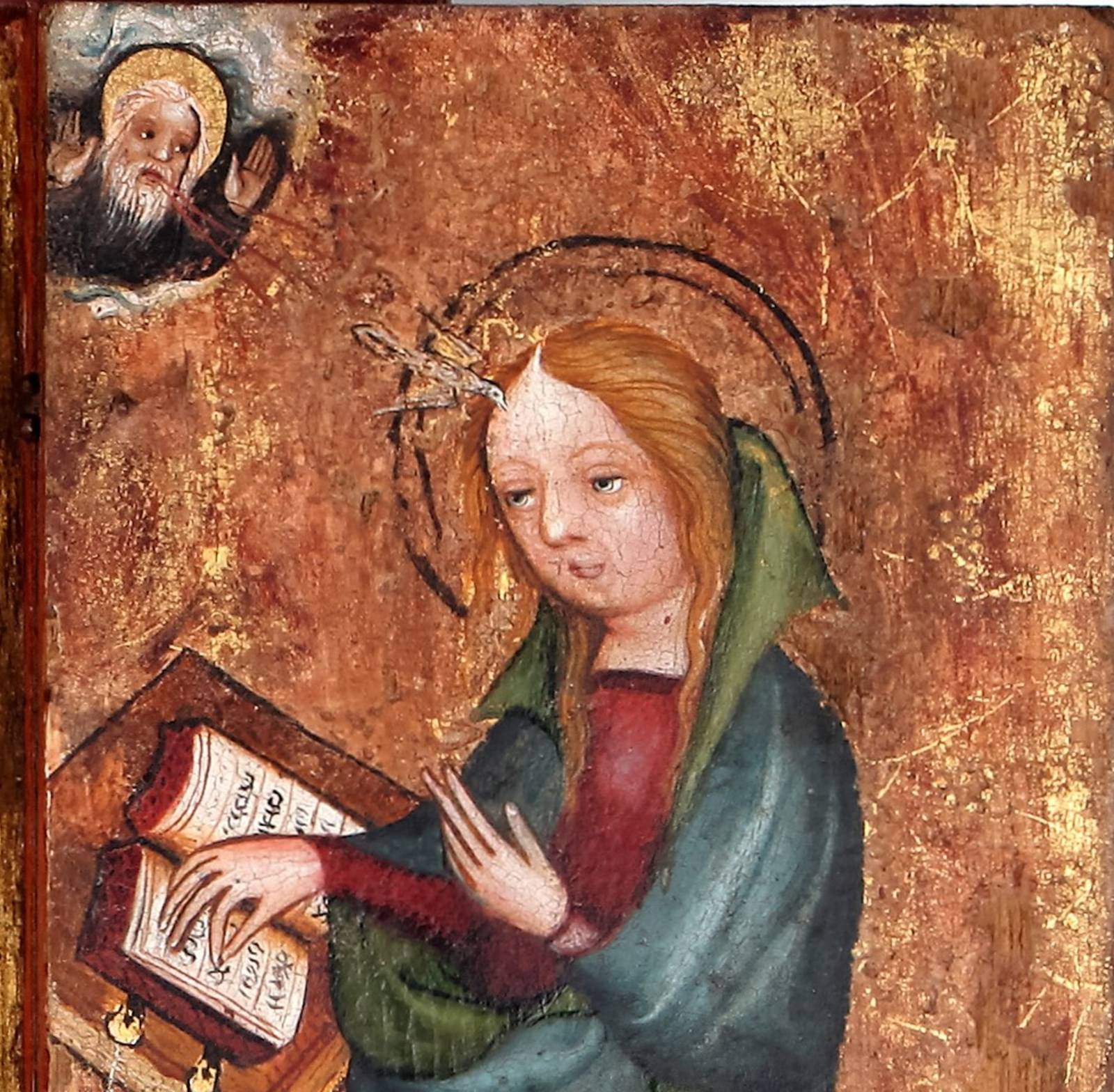

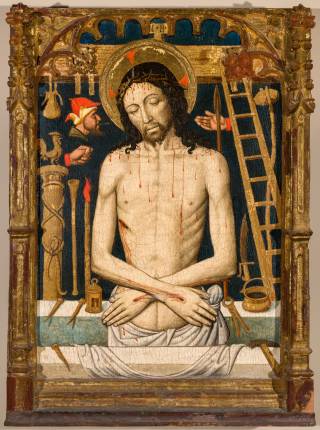

In February 2025, Godelinde visited the northeastern Dutch city of Enschede to present a lecture at the Rijksmuseum Twenthe. Held on 8 February, the talk accompanied the exhibition “Seeing and Believing: Sensory Experience in the Late Middle Ages”, which homed in on the role of the senses in medieval devotion. (The title of the exhibition references the adage “seeing is believing”) Particular attention in the exhibition was given to the role of objects, including manuscripts, and how these objects and sensory impressions may have informed religious experience. Different rooms explored different sensory modalities and encouraged visitors directly to encounter the highly (multi)sensory nature of medieval devotion: the exhibition included for instance, alabaster and parchment for the visitors to touch, chants to listen to, and pomander to smell. This multisensory nature of medieval devotion (and, by extension, lived religion) naturally raises the question of disabled individuals’ participation in such piety: how did medieval blind or deaf individuals, for instance, respond to religious practices demanding that believers gaze upon an image of Christ or listen to sacring bells or prayer?

Godelinde’s lecture, “What Accessible Devotion? What Medieval Women with Disabilities Can Teach Us Today,” approached these concerns through the writings of Low Countries nuns (the sister-books that Godelinde looks at in her “Cripping Sisterhood” project) and the analytical category of accessibility. The lecture mapped both the challenges and opportunities that devotion brought and the normative embodiment it expected, charting especially how lived religion inflected how the religious community and the disabled individual related to one another. However, the lecture also explored medieval instances of accessibility, and concluded by probing on whose terms such accessibility was offered, which constitutes a point of contact with modern debates. The talk centred on the lives of four medieval women: Sister Katharyna van Arkel (d. 1451) a blind Sister of the Common Life from the Master Geert’s House in Deventer; Sister Stijne Goringhes (d. 1441), another Sister of the Common Life from the same community, who was hard of hearing; Sister Elsebe Hasenbroecks (d. 1458) an Augustinian canoness regular from the Convent of St Mary and St Agnes at Diepenveen, who develops a visual impairment and becomes hard of hearing; and Sister Beel te Mushoel (d. 1481), an Augustinian canoness regular from the Convent of St Agnes in Emmerich (present-day Germany), who lost an (already impaired) eye in an accident. In addition to considering the social bonds between the women in these communities and the quality of life of these women with disabilities, the talk frequently referenced the objects on display in the exhibition, thus texturing visitors’ understanding of these artefacts and increasing their awareness of the diversity of medieval society.

The lecture was a great success; no less than 105 people attended, and the event was almost sold out. Particular care was taken to make this event accessible, in keeping with the theme of the lecture: each image was described in sufficient detail and a transcript of the lecture was available for deaf and hard-of-hearing audience members. Presenting this lecture highlighted for Godelinde how, as the lecture concludes, accessibility in (lived) religion should never be an afterthought but rather a central consideration, one that assumes a diversity of ways of being in and experiencing the world.