PETER SÖDERLUND

Political trust in established democracies is generally lower today than it was three or four decades ago. In the short or medium term, there are fluctuations, up and down, due to political and economic events. For example, political trust decreased in many countries in the wake of the most recent global economic crisis.

In the Nordic countries, citizens still display a comparatively high level of trust in political institutions and actors. Even though trust levels have varied over time, the changes have not been as radical as in Greece, Spain and Cyprus.

The extent to which trust varies between countries and over time can be obtained from the European Social Survey (ESS), which has gathered data from over 30 European countries since 2002. The latest numbers, based on fieldwork in 2016, were published by the ESS in the end of October. Such an international survey program with nationally representative surveys that are repeated over time enable us to observe not only differences between countries but also changes over time.

Three of the questions ask for how much citizens trust in their country’s parliament, political parties and politicians. Responses were given on an 11-point scale, ranging from 0 to 10.

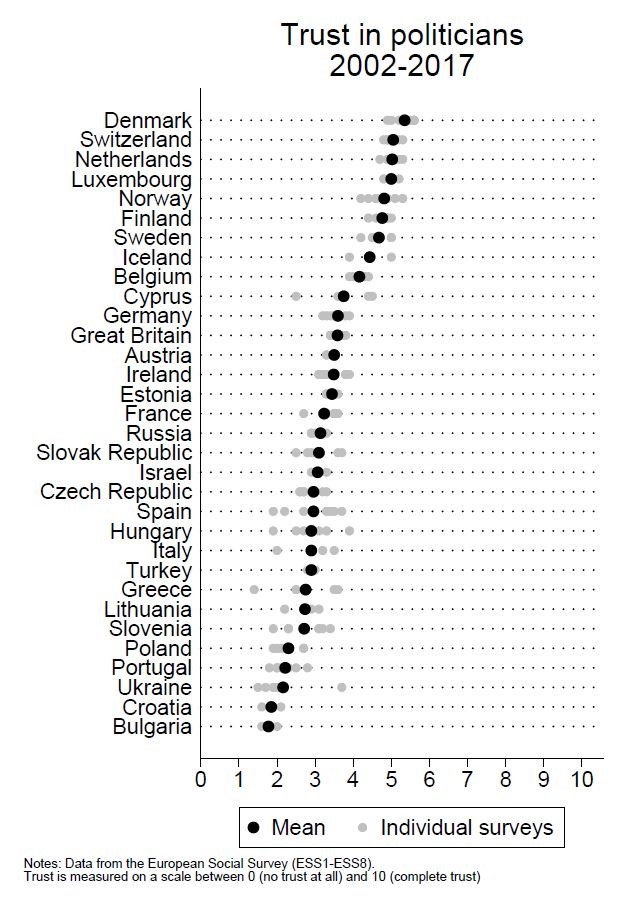

Figure 1 reports trust in politicians across 32 countries. Each black dot represents the mean of a series of surveys. Trust in politicians has been the highest in Denmark (5.4), Switzerland (5.1), Netherlands (5.0) and Luxembourg (5.0). These countries are followed by the four Nordic countries Norway (4.8), Finland (4.8), Sweden (4.7) and Iceland (4.4).

Very similar patterns are observed both for trust in the national parliament and trust in political parties. The difference is that trust in the national parliament tends, on average, to be 1 point higher than trust in political parties and politicians.

The grey dots graphed in Figure 1 are individual surveys. These show that there are differences over time. Yet differences between countries are more distinctive than differences within countries over time.

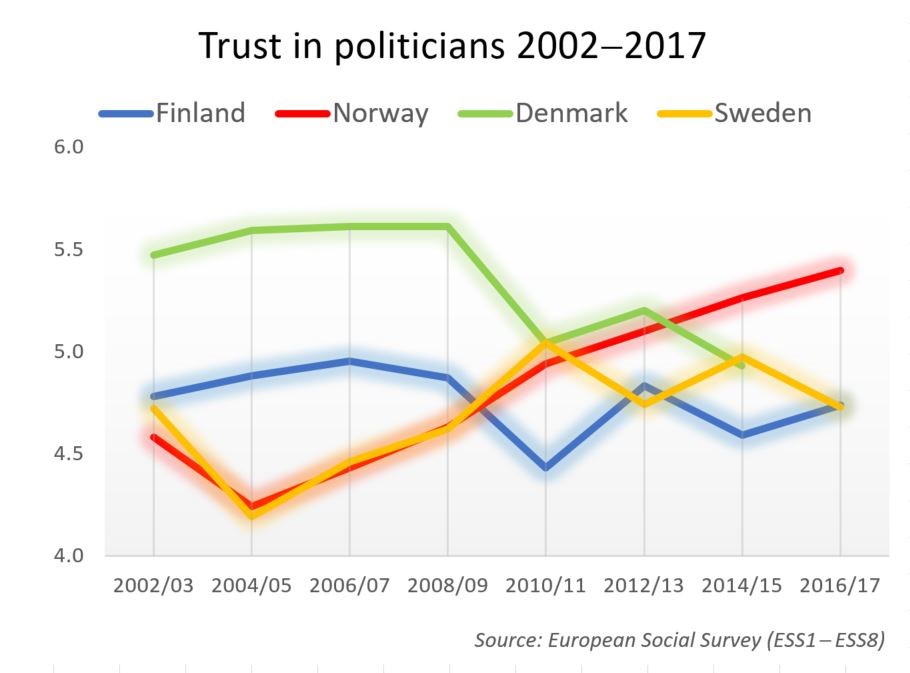

Finland, Norway and Sweden have participated in all eight survey rounds, while we at present time have data for seven rounds for Denmark. Figure 2 shows how trust in politicians has developed in these countries over the past 15 years.

In Finland, trust in politicians has fluctuated after the 2008/2009 economic crisis. The latest survey demonstrates a recovery in degree of political trust. Among Finns, trust in politicians was last year 0.3 points lower compared to the 2004–2008 period.

Fluctuations in political trust are also observed for Sweden and Denmark, even though the long-term trend is positive in Sweden and negative in Denmark. In Norway, the trend has been strongly positive since 2004. The Norwegians are the most trusting people in Europe today. It is evident from the data that increasing satisfaction with the government and satisfaction with the economy accompany increasing political trust.

Political trust has traditionally been high in the Nordic countries. Recent survey data thus show that although citizens appear to have a healthy scepticism towards political elites, no long-term decline in political support can be detected for the time being.

Peter Söderlund is Academy Research Fellow of the Academy of Finland and working in the Social Science Research Institute at Åbo Akademi University.

“It is evident from the data that increasing satisfaction with the government and satisfaction with the economy accompany increasing political trust.”

These are the usual variables, but have any new variables become more prominent or of reduced impact when it comes to political trust? For example, would there be a way to measure the relation of populism (e.g. popularity of populist parties) to trust in politicians. It would interesting to see if there was any correlation, since populist tend to leverage public distrust (or just dissatisfaction?) with establishment politics.

Mikko Poutanen

2.11.2017 17:53

Well, first of all you have to understand some basic things about causal mechanisms: a) there are external events that affect both political actors and citizens; b) some political actors (e.g. populist parties) may take advantage of the situation by publicly expressing their discontent in order to try to mobilize potential supporters; c) some citizens form their own opinions independently, while others take cues from opinion leaders (e.g. populist parties). To answer your question: we are empirically able to demonstrate how things are if we experimentally manipulate i) who is saying what and ii) how citizens react to different messages. This is one of the aims of the project.

Peter Söderlund

2.11.2017 22:37