AINO TIIHONEN

Why do people vote and what makes elections special? Is it possible to have democracy without elections? What is the relation between political trust and voter turnout? What is the role of political trust in voting and elections? Does high level of political trust automatically indicate high voter turnout?

The large scale societal changes reshape the attitudes and values of citizens’ continuously, which sets citizens interpret the political performances differently than before. We also know that satisfaction with the political system and its institutions affect the level of political trust, and that political trust is somehow a basic necessity of the political system. If people do not trust the incumbents or the political system, representative democracy provides a chance to exchange untrustworthy politicians through elections.

The main function of elections in a representative democracy is to select the representatives in the fairest possible way. Voting can therefore be seen as a “democratic ideal”. We could just as well use lottery instead of elections for the same purpose, and some actually like to think that a lottery would be an even more fair way of selecting representatives than elections.

Nevertheless, elections have prevailed. One golden argument in favor of elections is that in elections many candidates seek to be re-elected, which may make them pay more attention to voters’ opinions than they would in case of lottery. It is surprising how often voters assume that the representatives want to be re-elected. To put it simply, in elections voters give their representatives the right to speak on their behalf, a mandate.

The concepts of mandate and legitimacy raise questions of what actually constitutes a vote? A vote can be seen as a twostep process: first, the decision to vote and second, the decision of which party or candidate to vote for. Whether these are two different decisions is a different question.

Many things affect the vote, from socioeconomic factors to values and voters’ strategic considerations. The factors that affect the voting process are fertile fields for electoral studies. Nevertheless, before we try to find out what affects the second voting decision, the choice between candidate or party, we should pay attention to the first decision, i.e. the decision to vote in the first place. But what does turnout really tell?

High turnout in elections is often desired. The most common argument for high turnout is the representatives that it provides. Can we assume that a five percent turnout is as representative as a 95 percent turnout?

For instance, in surveys, the sample size is much lower than five percent of the total population but the survey sample is more representative. The difference between the election sample and the survey sample lies in the contingency: the election sample is not random in real life.

There are plenty of interesting questions arising from the theme of turnout, but in the context of political trust, we may ask whether voter turnout rates affect the level of political trust, and if so, what does it tell?

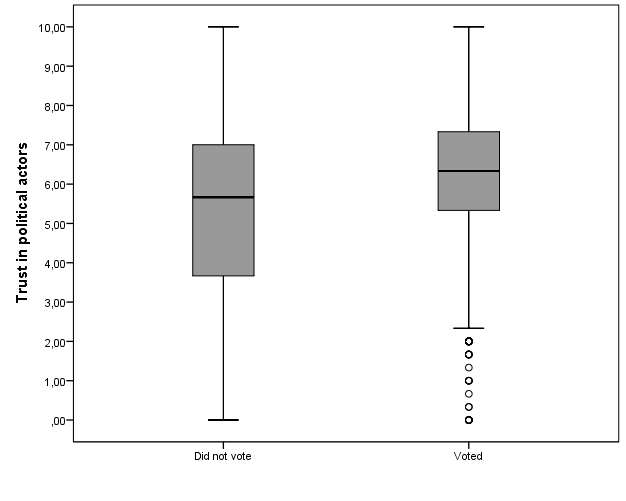

Figure 1. illustrates well how the people who voted in the Finnish parliamentary elections in 2011 were more trusting of political actors (sum variable: parliament, politicians, parties) than people who did not vote.

In this figure political trust is operationalized as specific trust in certain political institutions, such as political parties, politicians and national parliament. The two box plots display the distribution of trust in political actors between the Finnish citizens who voted in Finnish parliamentary elections in 2011 and those who did not vote. The green box includes the half (50 percent) of the all the observations. The black line illustrates the median. Since the green box of citizens who voted is higher than the green box of citizens who did not vote, we can rapidly notice that the citizens who voted trust more in political actors than those who did not.

We can cautiously assume that the level of political trust affected peoples’ decision to vote in the Finnish parliamentary elections of 2011. Even though the voters might have been dissatisfied with the incumbents, they could have thought that their vote had value since their trust in political actors was relatively high.

It has been observed in several studies that the correlation between political trust and voter turnout can be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the lack of political trust can motivate people to vote in elections, but on the other hand it can lead to the opposite result, which would mean that people might feel that a vote does not have an importance and even if they voted, the society and political climate would not change.

In addition to this, a high level of trust in political institutions, such as trust in parliament, might significantly increase voter turnout. There is no doubt that political trust and voter turnout correlate with each other. Since the relationship between these two variables is diverse and complex, it is also meaningful to study the topic of political trust in the context of electoral studies.

Aino Tiihonen is PhD student at University of Tampere. The topic of her doctoral dissertation is the changing relations between political parties and trade unions in the Nordic countries. She participated in the 2nd Leuven-Montreal Winter School on Elections and Electoral Behaviour which was held in Montreal, February 26 – 5 March, 2016.

Comments